“To love Jesus Christ is the greatest work that we can perform on this earth but it is a work and a gift that we cannot have of ourselves; it must come to us from Him and He is ready to give it to those who ask Him for it . . . A day will come . . . where we shall find united with us many hundreds of thousands of souls who at one time did not love God but who, brought back to His grace by means of us, will love Him and will be for all eternity a cause of gladness to ourselves. Should not this thought alone spur us on to give ourselves completely to the love of Jesus Christ, and to making others love Him? I finish but I could go on forever from the desire I have that I might see you all filled with love for Jesus Christ, and working for His glory. — St. Alphonsus Liguori, Founder of the Redemptorists Congregation

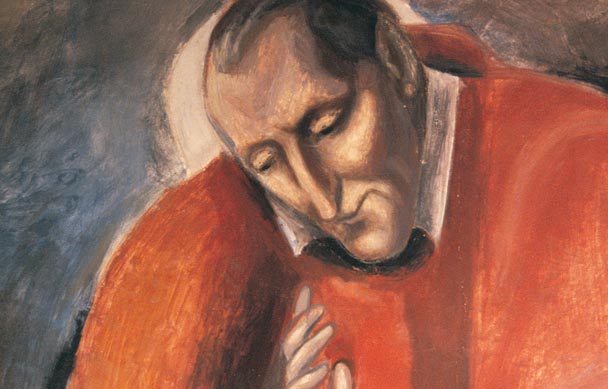

St. Alphonsus Maria Liguori was born September 27, 1696 in Marianella, near Naples, Italy. He was 16 years of age when he received his doctorate in civil and canon law. His father, a nobleman, had high hopes for his son, the eldest of seven children. Alphonsus was a prodigy; he easily mastered any subject put before him. By the age of 13, he was playing the harpsichord with the perfection of a master.

Poor health kept the young Alphonsus from following his father into the navy. His father decided the best course for his son, in order to attain a position of influence within society, was to become a lawyer.

For nearly 10 years, the future saint distinguished himself in the courtroom. Alphonsus was considered to be one of the up and coming stars of the Neapolitan bar. He never lost a case. Then, in 1723, in a lawsuit that would decide a property dispute between a nobleman and the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Alphonsus erred in the reading of a critical piece of evidence. He turned deathly pale. Then, in a broken voice, he announced, “You are right. I have been mistaken. This document gives you the case.”

He would never practice law again. Alphonsus spent the next several days alone and in prayer. One day, while visiting the sick at the Hospital for the Incurables, he found himself surrounded by a mysterious light. He then heard a voice say, “Leave the world and give yourself to me.” Alphonsus left the hospital and went directly to the church of the Redemption of Captives. There he laid his nobleman’s sword before the statue of Our Lady, renounced his inheritance, and made the decision to become a priest.

He was ordained a priest on December 21, 1726. Alphonsus would spend the next several years attending to the spiritual needs of the lazzaroni, the beggars and street people of Naples. Suffering from exhaustion, Alphonsus, on the advice of his doctor, left the city for the quiet of the countryside. On the Amalfi coast, he would meet another group of people abandoned by the priests of Naples, the goat herders and shepherds tending the hills above the Amalfi coast.

Back in Naples, Alphonsus was asked by his spiritual director, Bishop Thomas Falcoia, to look into reports of a nun’s vision concerning the creation of a new order of women. After speaking with Maria Celeste Crostarosa, Alphonsus determined she was doing God’s will and gave her efforts his blessing. Maria Celeste would then tell Alphonsus that she had experienced another vision, one that foretold of Alphonsus himself establishing an order of religious men. This would come to pass a year later, in November of 1732, when he established the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer, more popularly known as “Redemptorists,” whose mission would be to follow the example of Jesus Christ, the Redeemer, by preaching the Gospel to the poor (cf. Luke 4,14-21).

In March of 1762, the pope appointed Fr. Alphonsus as the bishop of St. Agatha of the Goths, a plum job in a well-to-do diocese with plenty of priests. But Alphonsus was not happy about it. Despite his petitions to be spared this appointment, he threw himself into the task, reforming abuses in the diocese, organizing general missions, and establishing social welfare programs for the poor, even opening his palace to the needy. But ill health forced him to give up the bishopric in May of 1775. Alphonsus also found himself caught up in the debate over two warring ideas of morality. His celebrated work, Moral Theology, argued for a middle position between rigorism and laxity. The Church sided with him, later declaring him a Doctor of the Church and the patron of moralists and confessors.

On August 1, 1787, Alphonsus died. In 1839 he was canonized. In March 1871, Pius IX declared him a Doctor of the Church, and in 1950 Pius XII declared St. Alphonsus the official patron of moralists and of confessors. He is also the patron saint of vocations and of people who suffer from arthritis.

He was also nicknamed “The Teacher of Prayer.” He developed his whole teaching on morality, holiness, and Christian living around his understanding of prayer. It can be summed up simply in his famous dictum: “The person who prays is saved, the person who does not pray is lost.” In other words, the ultimate success or failure of life centers on prayer.